on

A brief history of social media

How did social media as we know them today come to be? What would the world have been like if social media platforms had never been invented? Or was social media an unavoidable step in the evolution of the human species? These are hard -if not impossible- questions to ask. In this post we look at its forgotten history, to remind ourselves a fundamental truth about social media: that it is an historical phenomenon, and, as such, it is subject to change.

CompuServe's circa 1980 image of a high-tech future.

That of social media has been a revolution of unprecedented scale in human history. No technology ever developed has so radically penetrated the daily routine of half of the world (4.62 billion active social media users have been reported in 2022, datareportal.com). And social media has accomplished the deed in less than 20 years. We will see that the roots of this phenomenon trace back to the early stages of the information era (late 1960s), however I can anticipate to you that it is not before 2003 that we see the first signs of what has been an unforseen siege of society. Despite all the critiques that may be moved to it, the development of social media remains remarkable in its proportions and in this context it is undoubtedly fascinating.

Another aspect to consider is that the growth of social media cannot be explained by any tangible need: social media cannot be compared to agricultural or industrial technologies in this regard. One may even say that it cannot be compared with its closest partners, i.e. mobile phones and laptops, as they appear to possess the character of necessity that social media platforms simply lack. More to the strange case of the sudden spread of this “mania” on a blue and green planet rolling along somewhere in the Milky way: there was no political intention or careful planning of its development. Put in another way, the world population did not ask for social media: like any catastrophe, it just happened. Really, governments and the public service were probably the last piece of society to hop on the wagon. In hindsight, the development of social media can be regarded as part of the natural course of existence of a capitalistic and technologically prepared society as ours in the early 2000s. In fact, although the process that brought our ‘social society’ to be may seem completely erratic and extraneous to our nature, its mechanisms heavily rely on simple instincts common to every human being.

Chap I. The origins

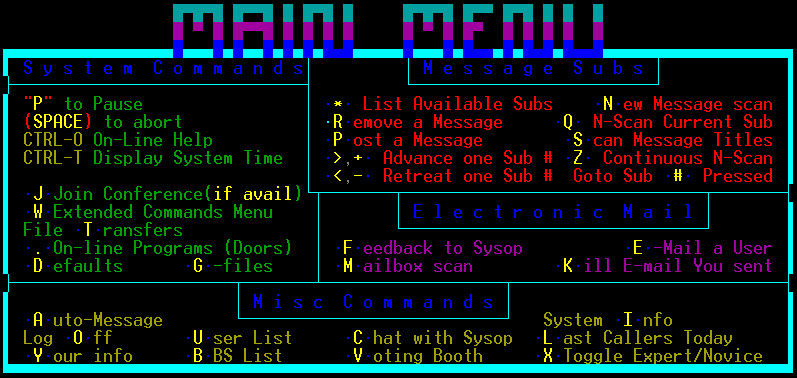

Social media as we know it today has almost nothing to do with its origins. It was born as a very exclusive activity: most of its users had to be serious computer hobbyists or commercial clients because the system required rather complex skills to be operated. Many of you will know that the very first connectivity effort -which eventually led to the birth of this magic place called The Internet- was part of a U.S. Department of Defence project (known as ARPANET) whose aim was to connect universities on a proto-internet. Yes, thank the cold war happened if you enjoy browsing around. The project, started in 1962, produced its first message in 1969: funnily enough the message sent was simply “LO” instead of the intended word “LOGIN” as the system crashed halfway through (historyofinformation.com). Albeit of fundamental importance to this story, ARPANET cannot be considered part of it, simply because it is missing one of the most characteristic feature of “socials”: to be used during free time, as a form of entertainment. The first non-military computer-based community was born 10 years later, in 1978, when the Computerized Bulletin Board System (CBBS) (Wikipedia) was created. Its authors, Ward Christensen and Randy Suess, thought of it as an electronic version of the type of bulletin board found on the wall of many work places: the main purpose of the technology was to post simple messages between users. The BBS became the primary kind of online community through the 1980s and early 1990s, before the World Wide Web arrived. [For those of us who cannot remember these times, a “vintage” documentary produced in 1992 by Roy Janke can help our imagination.] Using a BBS was not easy, even after GUIs (graphical user interface) were introduced: users had to be professional system operators, and accessing boards was charged with long-distance phone fees. The most advanced BBS offered uploading and downloading functions for software and data, news and bulletins reading and message exchanges with other users through public message boards, and in some cases via direct chatting. At its peak, this technology supported 60 thousand platforms serving 17 million users in the U.S. For some people this was a hobby, but for the most this was a rather unappealing way to spend your free time (like, say, home brewing).

Chap II. Before Friendster: the '90s

Fast-forward 20 years. We’re in the 90’s and the World Wide Web is born thanks to a British researcher (Tim Berners-Lee, Wikepedia) working at CERN in Switzerland. As an increasing number of people was gaining access to the Internet (thanks to the advent of commercial personal computers and their widening market, Wikipedia) a plethora of precursors of social media sites were born. Yahoo! Geocieties (1994-2009), originally called the Beverly Hills Internet, allowed users to create and publish websites for free and to browse the other user-created websites. In 1999 it was supposedly the third most visited website on the World Wide Web. What made GeoCities unique was its original organisation of the user-generated content into cities: for example, computer-related sites where displayed in “Silicon Valley” and those dealing with entertainment were assigned to “Hollywood” - hence the name of the site. Sixdegrees (1997-2001) arrived a few years later but eventually acquired an equivalently wide popularity. The name refers to the six degrees of separation concept, attributed to the Hungarian author Frigyes Karinthy, according to which all the people in the world are 6 or fewer social connections away from each other. On the website, users were asked to list friends, family members and acquaintances (which would then be invited to join the site too) and, in addition to the possibility of exchanging messages and bulletins with the users in their closest circles, they could see their degree of connection to any other user on the site. Another noteworthy example is the AOL Instant Messenger (1997-2017), abbreviated AIM. Its main distinguishing feature was the exceptionally advanced instant messaging technology, which allowed users to communicate in real time. Over the years it developed a list of useful features, some of which form the skeleton of today’s messaging apps. To name a few: the “buddy list”, user profiles, voice chat and file transfer. The website reached 18 million users at its peak. [Side note: on Mashable you can find an in-depth look at the rather controversial history of AIM.]

Many other sites blossomed during these years, sharing more or less the same characteristics. Why so many? Most of these platforms were offering forum-like discussions, where to talk about particular topics with complete strangers, and minimal user profiles, where you could insert one or two pictures and enter a few personal details (for the youngest in the audience, picture Reddit, but smaller). In a nutshell, social media were boring at this time: after having completed your registration and maybe invited your friends there wasn’t much you could do. My guess is that most of the people would just keep re-iterating this process on a different website, enjoying the small variation in style and functionality. This could explain why so many similar platforms were created in such a short period of time.

.png)

The most popular websites at the time were instead offering a very different user experience, often answering specific user’s needs. Among them, Live Journal (1999-) offered web-hosting services for users interested in blogging: differentiating it from the rest was its open and customizable writing format. Perhaps funnily, it was started by the American programmer Brad Fitzpatrick to keep his high school friends updated on his activities and it ended up becoming the main blogging tool in Russia. In 2006 the website was sold to a Russian company, which still owns it today. The history of the web writes in detail on the story of this website and its bizarre ties to the early 2000s international politics.

On a different note, Napster (1999-) was a file-sharing network specifically designed for music files (in MP3 format). Many platforms were already offering file-sharing, but Napster stood out for its focus on music, its user-friendly interface and its rather unusual choice to rely on a peer-to-peer sharing technology (the same in use by most pirate websites today). The platform registered an instant success, reaching 80 million users at the height of its popularity, by and larg anticipating today’s streaming platforms. Napster opened the world of music to the world, without asking, and this got some people really angry. Its service didn’t last long due to the numerous lawsuits (from music giants like Metallica and Dr. Dre) over the unauthorised spread of copyrighted material that started raining on its 3 young authors (brothers Shawn and John Fanning, along with Sean Parker) immediately after its release. But most failed to see that Napster had initiated a revolution that would radically transform the music industry in the following years. Between 2000 and 2010 music sales in the U.S. dropped 47 percent (CNN money). Finally, after a long court battle, the RIAA (Recording Industry Association of America) obtained an injunction from the courts that forced Napster to shut down its network in 2001. (This old tape from Headline News captured the public sentiment on the phenomenon at the time.) The following year, the website was sold to the digital media company Roxio, and transformed into an online PressPlay music store. [Side note: in 2003 Apple released the iTunes Store, in 2006 Spotify was founded in Sweden. It took the music industry 10-15 years to figure out how to profit from the ‘Napster model’: sometimes timing is essential.]

In summary, at the end of the ’90s social media were growing, but they were still a niche phenomenon. Simply put, they were not interesting enough for the users. The number of internet users was steadily rising, and along with it the number of active social media users. All the elements were in place for a revolution.

Chap III. The Friendster revolution

We’re in 2002 and the Canadian programmer Jonathan Abrams has founded a new social media platform called Friendster. Its name derived from the two words “friend” and (yes, you guessed it) Napster, and it offered scant user profiles, personal chats and music sharing. All in all, its features were not new: they had already been previously implemented and were available on various other websites. What happened next is probably going to surprise you. Friendster became the largest growing business in the history of social media at the time, breaking all the records, and arguably inaugurating a new era. Officially launched in 2003, it reached 3 million users within the first few months. Mr. Abrams suddenly found himself on the cover of multiple magazines and interviewed on late-night talk shows, while publications including Time, Esquire, Vanity Fair, Entertainment Weekly, Us Weekly and Spin were writing about Friendster’s success. For the first time since their appearance on the web, social media platforms had turned a nerdy Mr. Nobody into a rich and famous entrepreneur. What had started as a niche, unpopular pastime activity for computer hobbyists had now entered the room of serious businesses (to stay). In 2003 Google offered $30 million (in Google stock) to buy out Friendster: Mr. Abrams turned down the offer. But the platform was not ready to bear its own success: Friendster had major technology problems (as the same Abrams tells in an interview, “people could barely log into the website for two years”). Friendster was destined to be drowned by the gigantic wave it itself had started. In 2011 it was transformed into a social gaming platform, to be definitively shut down in 2015. The story of Friendster is a bitter testament to missed opportunities and lack of vision: had he acknowledged on time the potential of his small venture, Jonathan Abrams could have gone down history as one of the world’s most successful tech founders. Someone else did instead.

A 19 years old college student from New York saw the opportunities hanging from the social media tree and moved quick to seize them. The race to overtake this newfound market had officially started.

Chap IV. After Friendster: today pt.1

Most of the readers will have personally witnessed the remaining part of this story. In the span of two calendar years the social media market experienced a growth that had taken decades to unfold in other business sectors. Between 2003 and 2005 a number of tech-giants-to-be such as MySpace, LinkedIn, Second Life, Flickr, Facebook, Youtube and Reddit were founded. Most interestingly, the way users interacted with social media websites underwent a fundamental shift, and with it the collective perception of these new web services changed. Suddenly, more and more people began spending hours every day on once boring websites. During the second half of the 00s the foundations for the imperishable success of social media were laid: multiple platforms started experimenting with new features built to maximise the user’s engagement, capitalising on blameless research in psychology. To his merit, Mark Zuckerberg was the first to discover and develop many of the ingredients that would make social media companies dangerously powerful. [It is natural to wonder at this point whether social media would have been the same had Mark Zuckerberg decided to spend his life selling ice cream instead.] A 2019 study (PMC) published on the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health has analysed the main psychological mechanisms responsible for creating addiction to social media: most of the addictive features discussed in this study were first introduced on the platforms between 2006 and 2009. In the dedicated section below we take a deeper look at these features and the underlying addictive mechanism, but first a few key events marking the years between 2005 and 2010:

-

In January 2007, Apple Computer introduced the iPhone (Apple’s article), the first smartphone that would revolutionize the mobile phones’ market (previous attempts at smartphones had not been as successful, Wikipedia). Unintentionally, smartphones played a crucial role in the evolution of social media: probably Facebook would not have become the business giant it is today if it hadn’t had the chance to move into our pockets and follow us around. [Unrelated side note: do you remember the cost of the first iPhone? $499, in its less expensive version.]

-

In November 2007 Facebook introduces Facebook Ads (Facebook’s article), an advertising system allowing businesses to create individual profiles, mimicking the functions of a standard user. Before that, Facebook had reluctantly incorporated ads into empty screen spaces (the service was known as Facebook Flyer and it was introduced as early as only 2 months after the foundation). This small change made a world of difference to the advertisement industry, effectively ushering it into social media.

-

In April 2010 Marck Zuckerberg announces GraphAPI v1.0 at the Facebook F8 conference (CNET), an interface that accomplishes two feats: on one hand it lets the users access most websites and apps with their Facebook identity (the great “login with Facebook”); on the other hand it allows the sites’ developers to directly collect information on their users from their Facebook profiles. Sounds like a win-win. The API release was met with enthusiasm by most web services (infoq.com), which would advertise it as a step forward in the spirit of “web openness”. Basically, once authorised with an innocent-looking prompt, any website or app could retrieve, store and process people’s data (posts, likes, pictures, … ) - including that of their friends’ network - theoretically forever. It was an unacknowledged revolution in large-scale data provision, marking a fundamental shift in social media’s business model: from ads- to data- centered. The scraped data allowed multiple businesses to deliver targeted advertising and, in general, transformed social media into a powerful instrument of social control, as the Cambridge Analytica scandal would later prove. To some extent, the release of the first Graph API can be regarded as the birth of modern social media: welcome to the era of low-key mass manipulation! Facebook eventually closed the Graph API v1.0 in 2014, promising to “put people first” in future platform developments (Facebook’s announcement).

Intermezzo. Addictive features in social media.

Endless Scrolling/Streaming and the Concept of Flow

You may not remember it, but Facebook pages used to have an end. Aza Raskin invented endless (or infinite) scrolling in 2006, when he was working at Humanized, a company focused on improving user-experience on webpages. In a presentation (still available in some remote corner of the web) he pitches the idea behind this new feature as follows: “don’t force users to ask for more content, just give it to them”. Today Mr. Raskin regrets his invention. Quoting from one of his tweets: “One of my lessons from infinite scroll: that optimizing something for ease-of-use does not mean best for the user or humanity.”. In 2013 he co-founded the Center for Humane technology, a nonprofit organisation dedicated to radically reimagining the digital infrastructure.

Endowment Effect/Mere Exposure Effect

The endowment effect is generally defined as the increase of the perceived value of a product after its purchase. Simply put, the more you invest in something, the more that thing matters to you. Translated in the context of social media, the endowment effect increases the interests of the users in the platform as the platform is being used (e.g. chatting, discovering news or modifying one’s profile). For a familiar example of the effect in action think of Instagram: after sharing a new Instagram story or Instagram post the user is more likely to come back to the platform than the usual. Both ownership and loss aversion are discussed as reasons for the endowment effect. The exposure effect often works in conjunction with the endowment effect: simply, the increase in familiarity with the service leads to increased user enjoyment. These two mechanisms naturally play in favour of user engagement as the usage increases: thus the real challenge for social media companies was persuading the user to come back to the platform often enough.

Social Pressure

Feeling compelled to answer a text because of the read receipt, or peaking at the message from the notification bar to avoid committing to an answer are both good examples of social pressure at work, the third mechanism mentioned in the study. It spontaneously emerges when both sides know the rules of the scenario. For example, both parties are likely to expect an answer to arrive shortly after a message has been read: in this way social pressure nudges the users of messaging apps towards faster communication. Likewise, sending one text often bears on the user an unacknowledged commitment to a dialogue for the following 5-10 minutes (translating into more usage). This principle has first been put to use by Apple in 2011 (Apple keynote), followed by Facebook in 2012 (CNET), albeit with an essential difference between the two: Apple iMessage read receipts were optional, Facebook Messenger’s weren’t (theguardian.com). Interestingly, WhatsApp introduced read receipts in 2014, the same year it was acquired by Facebook.

Show Users of an App What They Like

Undoubtedly, Facebook’s most successful bet has been its visionary NewsFeed, which during the years has housed masterful engineering efforts, often advancing the state-of-the-art technologies on automatic profiling and natural language data analysis. The platform didn’t have a NewsFeed until 2006. Before its introduction people would have to intentionally navigate to their friends’ personal pages to see their updates: basically the site was little more than a directory of names, interests and contact information (difficult to picture today, right?). The Feed simply reorganised and summarised the recent updates from the user’s friend list, displaying them in a compact way on the new website landing page: it was meant to spare the users from the hustle of having to tour all their friends’ personal pages to get an overview of ‘what’s going on’. Remarkably, when it first came out, the NewsFeed was met with a lot of indignation from the platform (the popular opinion at the time was perfectly captured by Wired). The reason is that users were feeling exposed, every small update being automatically showcased to their entire friends’ list. [A small clarification is of essence here: the news shared on the feed corresponded to what was already made available to the public on the personal profiles, no private information was being disclosed.] Funnily, in response to the general unrest founder Mark Zuckerberg wrote a blog post called “Calm down. Breathe. We hear you” (mashable.com), but the News Feed stayed.

During the years, what was an innocent website reorganisation would become the powerhouse of the company’s most lucrative plans. After the introduction of the Like button in 2009, Facebook began developing algorithms to automatically select and organise the information available to the user. The selection would be based on the user’s taste, inferred from the personal ‘like’ records, the analysis of the emotional content consumed and other digital traces. The NewsFeed was tailored to each individual user, displaying the platform’s content in decreasing order of estimated engagement. As pointed out in a recent study (acm.org), with time and the increasing sophistication of the profiling algorithms, social media users became increasingly reliant on the automatic selection of the platforms’ content, often ignoring the underlying process. In other words, social media users today are less capable or less willing of choosing their content than their predecessors. We could deem the so-called personalised NewsFeed an additional service to the users, sparing them the time to go through posts that they would anyway find tedious. But the real gain is in for the platform: by excluding potentially boring content from its feed, Facebook significantly reduced the incentive to leave the website. Showing people what they like is among the most addictive features implemented on social media platforms today.

Social Comparison and Social Reward

The final mechanism to be mentioned in the study is the pair social comparison - social reward.

Social reward is what you experience when someone ‘likes’ your Facebook post or ‘hearts’ your new Instragram picture. This positive social feedback feature too was pioneered by Facebook (although some allegations suggest that it had been first introduced on Friendfeed), with the Like button launched in 2009 (launch blog post), although the project had been first developed internally in 2007, under the name “Awesome feature” (on Quora you can read the inside story of the Like button). Multiple neuroscience studies have demonstrated a significant addictive component in social reward mechanisms like the Like button (pubmed 1, 2, 3), especially among adolescents [pubmed]. [Side note: ironically, one of the five creators of the Like button, Justin Rosenstein, later deleted the Facebook app over addiction fears, Independent article]. Social comparison also plays a fundamental role in increasing social media app usage. The term refers to the tendency of using other people as sources of information to determine how we are doing relative to others, or how we should behave, think, and feel (sagepub). A study by the University of Toledo (psycnet) found an association between social media usage and self-esteem, with higher usage in a context of upward comparison being correlated to low self-esteem. Sadly, social comparison is a natural human instinct, and the unique opportunity of comparison offered by social media platforms promptly made them essential instruments of our social life. As of today, not having a Facebook, Instagram or Twitter account can pose a serious threat to the social fitness of an individual, especially earlier in life. In summary, social comparison and social reward can trigger psychologically dangerous spirals that progressively compel the oblivious user to revisit the platform.

Chap IV. After Friendster: today pt.2

The effects of the masterful albeit quiet transformation that social media underwent between 2005 and 2010 can be read off the many statistics on digital products published every year. datareportal.com is one good source for such statistics, providing a variety of free reports every year which can offer insightful new perspectives on the digital phenomena that we are contributing to create. Let’s look at some numbers.

- According to the 2022 global overview report there are 4.62 billion active social media users today, 424 million of which (10.1%) joined only in 2021. That sums up to 58.4% of the global population, a percentage that goes up to 74.8% when you exclude all those younger than 13.

- The number of people using social media has grown by 211% in the last 10 years.

- On average the internet user aged 16 to 64 spends 2h and 27 a day on social media today, compared to 1h and 37m in 2013. [How much is too much? BBC Future polled its followers on this question.]

- 3 Meta platforms occupy the top three places in the “favourite” social media platform rankings. In decreasing order: WhatsApp, Instagram and Facebook. Interestingly, the exceptionally growing platform TikTok ranks only 6th in this classification despite being the most downloaded app of 2021.

- The latest data suggest that TikTok has been adding an average of more than 650,000 new users every day over the first 3 months of 2022, which equates to almost 8 new users every second.

The matter gets more bizarre if we widen our perspective. According to the Global Digital Reports’s estimates, if the digital trends of the past year are maintained, our species will (globally) total more than 12.5 trillion hours online in 2022. All the way from bacteria, fishes and apes to get to digital freaks: what a spectacular evolutionary journey. But there’s more to be amazed at. A techjury report tells us that we produced 2.5 quintillion (add 18 zeros) data bytes per day in 2020. Think about it: the efforts of some of the best engineers on the planet are focused on the design of increasingly efficient data storage services, e.g. like the Open Compute Project, for us to keep uploading “stuff” on the Internet every day. In the words of PayPal co-founder Peter Thiel:

We wanted flying cars and instead we got Twitter.

5. Tomorrow

The rest of the history of social media still has to be written. The pressing question now is: what will it be about?

In its distinctively masterful way, the British TV series Black Mirror attempted to answer this question in Episode 1 of Season 3, Nosedive. The episode contemplates a future where the users are completely and irreversibly subjugated by social media platforms, and the storyline follows the main character, Lacie, in an unintentional quest for freedom. The scenarios created by Black Mirror often seem too drastic to ever be true, but they nonetheless manage to spark a feeling of unrest in the audience for their “dark” parallels with the present. Whether you share the grim outlook of Charlie Brooker (the episode’s writer) or not, watching Nosedive leaves you with the doubt: can it really get this far?

I have good and bad news for you. The good news is that if you’re reading this now (around the year 2022) you will likely be part of the answer. Ultimately, social media websites are what their users decide to do with them. “Smart” algorithms can only go so far, it is still up to you to choose what kind of content to share, what to look for and what to avoid. In a word, power is in the hands of the users. Quoting the wise uncle Ben, “with great power comes great responsibility” and this responsibility can only be leveraged by those who recognise social media as a fundamentally historical phenomenon and, as such, are ready to see it (radically) change. The bad news is that this is only partially true: the roots of social media spread so far into the financial fabric of our society today that the situation is really out of anyone’s hands. As it happens typically with tremendously lucrative affairs when they are discovered in a purely accidental and unexpected manner (see the European colonization of the Americas for a historic precedent), everyone quickly joins the race blided by their self-interest, without questioning the rules of the game. Although the parallel is hazardous in many respects, early social media websites like Friendster have been the Guanahani of the 21st century, and our species has not failed to show its natural tendency toward barbarity in exploiting its potential.

The point is that we need to talk about ethics in social media. Some voices have already started to be heard. You may have stumbled across the popular 2020 documentary The Social Dilemma, which unapologetically denounces the addictive nature of most social media platforms. Tristan Harris, one of the faces of the documentary, started discussing ethical design principles for SMS in 2013, when he was working as a design ethicist at Google. In a talk, titled “A call to minimise distractions & respect users attention”, Harris drafts a list of principles for future social media. I encourage you to take a look. Since then, he, together with Aza Raskin, and Randima Fernando founded the Center for Humane Technology with the purpose of encouraging the development of “humane technology”, that is to say a technology that priorities human values such as well-being, democracy and shared information. The views and discussions that they promote (through their website among other mediums) are refreshing and inspiring. As an example, their posts look at alternative business models for tech companies or analysing the global impact of platforms like TikTok. The spread of this new awareness has started to have a concrete impact too: since 2018 several major tech platforms have introduced “Time Well spent” features; Instagram has developed the “You’re all caught up” message, while Youtube has added a “Take a break” reminder to its platform, and since iOS 12 Apple has equipped its devices with tools to help the user better control its time. In a nutshell, this initiative tells us that it is possible (and, I believe, also our duty) to think differently, and imagine a new future for social media. I believe that technology can operate for the common good, strengthening our capacity to tackle the global challenges that lie ahead of us. What about you?

Our journey ends here. I hope you had some fun and that I could offer your attention useful content for future casual chats. Mostly, I hope that this article could persuade you that social media is an historical rather than a natural phenomenon, and as such it is not something for us to accept but something for us to change. Social media platforms might one day leave our side just as suddenly as they have joined it. It is possible, however, that they are here to stay for a very long time. Looking at the historical evolution of the phenomenon, which is unprecedented for the speed of its expansion and its pervasive and chameleonic nature, one can hardly draw any parallels with other societal changes in human history. In practice, we are at a loss of conceptual tools to predict its future. This is why it is crucial to carry on the discussion that Tristan Harris started in 2013: what principles should characterise the future of social media? As the physicist Dennis Gabor used to say, the only way to predict the future is to invent it.